A real German grammar challenge are the Wechselpräpositionen: two way prepositions, or as we prefer to call them two-case prepositions. These typically cause a lot of confusion. But once you understand how they work, they are actually very logical and easy to handle. In this article you can also see that we have recruited the help of a couple of flamingos to help you memorize the two-case prepositions.

So What are Two-Case, or Two-Way Prepositions?

We all know this German grammar challenge can be a pain in the a**, and two-case prepositions seemingly make this more difficult. Two way or two-case prepositions are a group of prepositions (i.e. tiny little words that make no sense and are therefore hard to memorize) that cause a change in the articles (den, dem etc.) and adjectives (schön, gut, groß etc.) that follow.

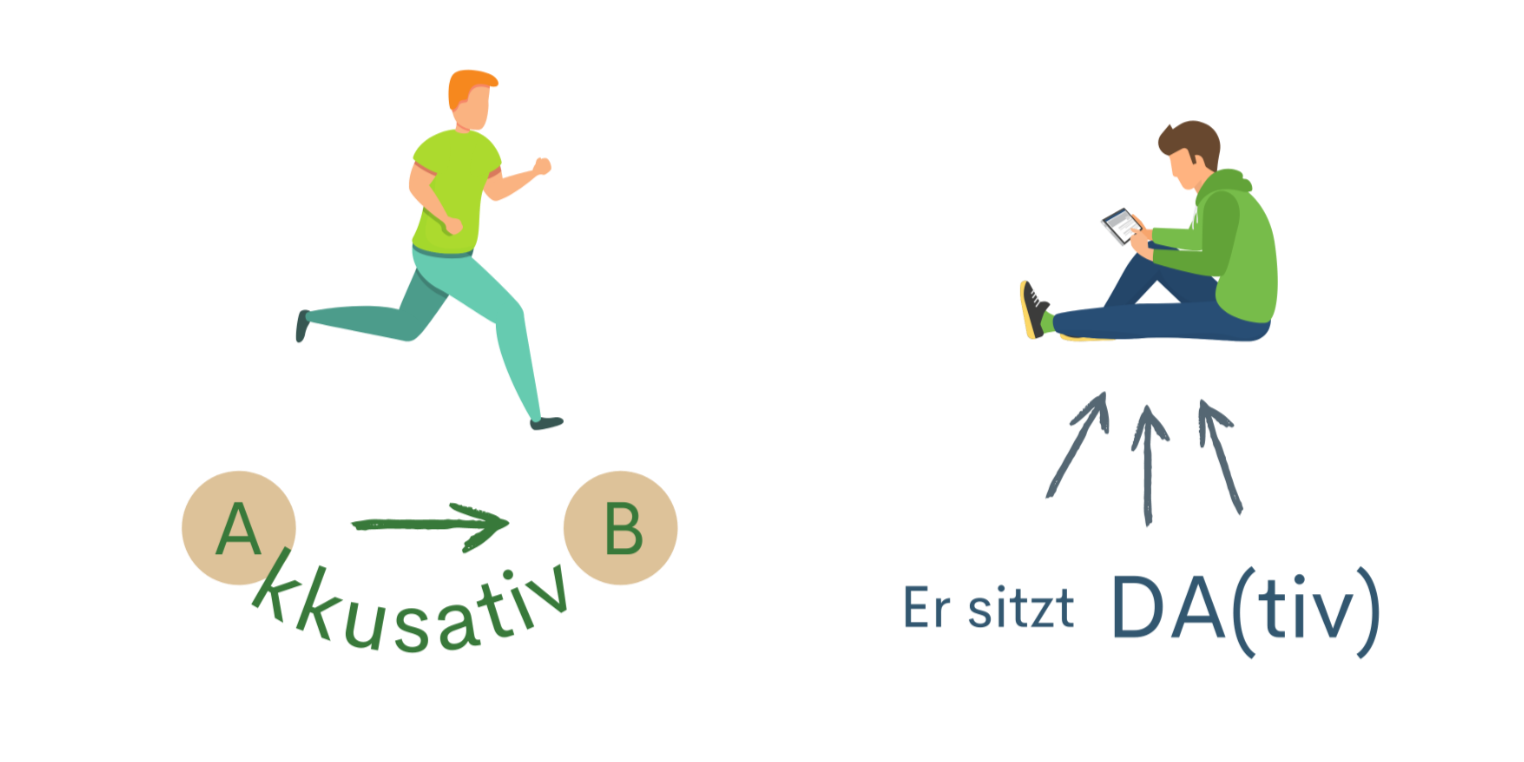

That change is important and is called Akkusativ or Dativ. Akkusativ and Dativ are so called cases. In German we have 4 of those cases, the other two are Nominativ (which is the basis and very straightforward) and the Genitiv (which is irrelevant, as it’s hardly used).

As the name two-case prepositions might give away already, these tiny little words can be followed by either of the two cases above: the accusative case or the dative case. This is also why they are often called two-way prepositions. They are also tricky because quite often you have to use a different article for the same prepositions.

However, one doesn’t really know when to pick which case in a certain prepositional phrase. Lucky enough, Hans Deutschendorf, the inventor of the two-case prepositions, has invented a rule for them.

A | If it moves from A to B you use the accusative case

B | If it is a static position (in the physical world) you use the dative case

Some German Two-Way Prepositions

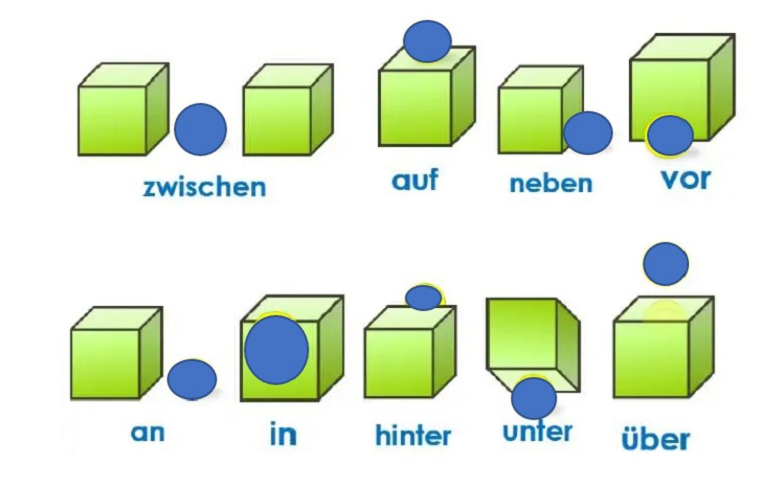

Here are some German two-way prepositions with an English translation:

an (on [vertical surface])

auf (on top of [horizontal surface])

hinter (behind)

in (in)

neben (next to )

entlang (along)

über (above)

unter (under)

vor (in front of)

zwischen (between)

Is the Preposition Dative or Accusative? How to Decide

When grappling with dual prepositions in the German language, discerning whether to use the accusative or dative case hinges on the type of question they answer. If the preposition addresses ‘where to?’ (wohin?) or ‘what about?’ (worüber?), it takes the accusative case. On the other hand, when responding to the question ‘where’ (wo?), it requires the dative case.

In essence, accusative prepositions in German typically denote an action or movement toward another location. Conversely, dative prepositions signify a static location or something not undergoing a change in position. For instance, consider the English phrases ‘he jumps into the water’ and ‘he is swimming in the water.’

The first one answers a ‘where to’ question, indicating movement from one place to another. In German, this is expressed as ‘in das Wasser’ or ‘ins Wasser,’ utilizing the accusative case.

The second phrase represents a ‘where’ scenario, indicating a static location. In German, it is conveyed as ‘in dem Wasser’ or ‘im Wasser,’ using the dative case. Here, the individual remains within the body of water without moving in and out of that particular location.

English vs German Prepositions

To convey these distinct situations, English uses different prepositions (‘in’ or ‘into’), while German uses a single preposition—’in’—accompanied by either the accusative case (for motion) or the dative case (for location). Speakers of English who want to learn German should keep this difference between the two languages in mind and try to decide which the correct case will depending on the different meanings they want to convey.

An Example of Two-Way Prepositions

A | Ich fliege in die Türkei. – die Türkei is Akkusativ as it follows “in” which is a two-case preposition and as flying means that one is moving from A (Berlin) to B (Türkei).

B | Ich bin in der Türkei. – der Türkei is Dativ as it also follows “in” but now I (=ich) am (=bin) in Turkey already. No more movement is necessary. I’ll just lie down and smoke my shisha.

Makes sense? So, if the preposition describes a location or a state of being, it takes the dative case. Here is another example: ”Das Bild hängt an der Wand” (The picture is hanging on the wall).

However, if the preposition describes directed movement (that is, movement towards a destination or a location), it takes the accusative case. For example, “Ich hänge das Bild an die Wand” (I’m hanging the picture on the wall). Another pair of examples would be, “Er läuft in dem Park” (having a walk inside the park, which implies the movement remains within the same location), while “Er läuft in den Park hinein” specifies that the person is not currently in the park but is running into it.

It’s also important to note examples where the meaning implies no literal movement is being described, but rather a change in state:

Die Raupe hat sich in einen Schmetterling verwandelt. (The caterpillar transformed into a butterfly.)

All this is covered in my Magnificent German Bundle which includes all language levels leading from A1 to C1. You can learn step by step and make yourself gradually familiar with the concept. That’s important so that you don’t get overwhelmed or confused.

Example Sentences

Here’s a breakdown of various dual prepositions in German, along with sample sentences showcasing both the dative and accusative cases:

- an (at, by, on):

- The Dative Case: Der Lehrer steht an der Tafel. (The teacher is standing at the blackboard.)

- The Accusative Case: Der Student schreibt es an die Tafel. (The student writes it on the board.)

- auf (on, onto):

- The Dative Case: Sie sitzt auf dem Stuhl. (She is sitting on the chair.)

- The Accusative Case: Er legt das Papier auf den Tisch. (He is putting the paper on the table.)

- hinter (behind):

- The Dative Case: Das Kind steht hinter dem Baum. (The child is standing behind the tree.)

- The Accusative Case: Die Maus läuft hinter die Tür. (The mouse runs behind the door.)

- neben (beside, near, next to):

- The Dative Case: Ich stehe neben der Wand. (I stand next to the wall.)

- The Accusative Case: Ich setzte mich neben ihn. (I sat down next to him.)

- in (in, into, to):

- The Dative Case: Die Socken sind in der Schublade. (The socks are in the drawer.)

- The Accusative Case: Der Junge geht in die Schule. (The boy goes to school.)

- über (over, above, about, across):

- The Dative Case: Das Bild hängt über dem Schreibtisch. (The picture hangs over the desk.)

- The Accusative Case: Öffne den Regenschirm über meinen Kopf. (Open the umbrella over my head.)

- unter (under, below):

- The Dative Case: Die Frau schläft unter den Bäumen. (The woman is sleeping under the trees.)

- The Accusative Case: Der Hund läuft unter die Brücke. (The dog runs under the bridge.)

- zwischen (between):

- The Dative Case: Der Katze steht zwischen mir und dem Stuhl. (The cat is between me and the chair.)

- The Accusative Case: Sie stellte die Katze zwischen mich und den Tisch. (She put the cat between me and the table.)

These examples showcase the nuanced use of dual prepositions in different contexts, helping to illustrate the distinction between the dative and accusative cases in German.

Getting the Case Right: Wo vs Wohin

Understanding the distinction between “wo” (where) and “wohin” (to where) is crucial when dealing with two-way prepositions. This difference determines whether to use the accusative or dative case in sentences using these prepositions. For instance, when describing movement within a specific location, like crawling under a table, the choice between the accusative and dative case depends on whether you inquire “Wo krabbelt das Kind?” (where is the child crawling?) or “Wohin krabbelt das Kind?” (to where is the child crawling?).

- an vs auf & der vs die Wand

When using prepositions like “an” or “auf,” the choice between accusative and dative cases can be nuanced. For example, when a person climbs a wall, the decision between “an” and “auf” hinges on the vertical nature of the object.

The case selection, whether accusative or dative, depends on the movement of the object in relation to the preposition. Additionally, when swimming in a pool, understanding the concept of motion helps determine whether to use the accusative or dative case.

- Direct Object vs No Direct Object

Differentiating between direct and indirect objects aids in deciding whether to use the accusative or dative case with two-way prepositions. Generally, if a sentence involves a direct object, the accusative case is used; otherwise, the dative case is applied. However, this is a generalization, and exceptions exist.

- Opposite Verbs

Certain verbs have counterparts that require either the accusative or dative case. For example, “legen” (to lay) requires the accusative case, while its counterpart “liegen” (to lie) involves the dative case. Similar pairs include “senken” vs. “sinken” and “setzen” vs. “sitzen.”

Oh No – Exceptions!

Unfortunately, there is one big problem with those rules above: they don’t apply to every situation. Take a look.

Special Accusative Prepositions

C | Ich denke an meine Mama. – I’m thinking of my mum. — Here “meine Mama” is Akkusativ and it follows the two-case preposition “an” but your thinking (=denken) is not moving physically from A-B.

The verb “denken” has nothing to do with the physical world (except that your Mama might be real). Hence, the rules above can’t be applied. But don’t worry, I’ll cover that nicely in one of my beautifully simple Master Classes which you find in my Everyday German Online Course.

Common Patterns

Much like in English, German also has specific verbs that consistently pair with particular prepositions. Take, for instance, the verb “to fall in love.”

In English, one falls in love “with” someone, not “about” somebody or “for” somebody. Similarly, in German, one falls in love “in” someone: For example: “Ich habe mich in sie verliebt.” (I have fallen in love with her).

While the preposition/verb combinations in German may not always align seamlessly, there are strategies to ease the challenge. To navigate this complexity:

Learn Both Together: When learning a verb, simultaneously learn the associated German prepositions and the cases they govern. Instead of merely learning “sich verlieben” (to fall in love), learn “sich verlieben in” (+ accusative). This holistic approach aids retention.

Memorize Examples: Emphasize learning through an example sentence for each preposition. Display signs around your environment with verb/preposition combinations to reinforce memory. For instance, “Achten Sie auf das Glatteis” (beware of the sheet ice) provides a visual cue to associate the preposition “auf” with the verb “achten.”

Tips on How to Use German Prepositions

Contractions:

Using preposition contractions makes you sound more native. Similar to contractions in English, these can be used in both spoken and written language. For instance, “an + das” contracts to “ans,” and “in + dem” becomes “im.”

Prepositional Adverbs:

Form prepositional adverbs by adding the prefix “da-” (or “dar-” if the preposition starts with a vowel) to a preposition. For example, “auf” becomes “darauf,” and “von” becomes “davon.” These adverbs refer back to something mentioned earlier, adding nuance and detail to sentences.

Prepositional Phrases:

There are lots of great idiomatic phrases that use prepositions and these are really handy in everyday speech. For example, include “Es kommt darauf an” (It depends), “Ich bin damit einverstanden” (I agree), and “Hör auf damit!” (Cut it out!). By incorporating these strategies and key terms related to fixed prepositions, cases, and verbs, you can enhance your understanding of German prepositions and use them with greater confidence.

Common Verbs to Describe Position vs Action

Let’s look at some frequently used verb pairs in German and how each of these prepositional verbs has a fixed case associated with it and typically pairs with either accusative or dative prepositions.

1. Stehen (to stand):

- Accusative: Der Mann stellt die Tasse auf den Tisch. (The man places the cup on the table.)

- Dative: Die Tasse steht auf dem Tisch. (The cup is standing on the table.)

2. Stellen (to place/put):

- Accusative: Ich stelle die Blumen in die Vase. (I put the flowers into the vase.)

- Dative: Die Vase steht auf dem Tisch. Ich stelle die Blumen in die Vase. (The vase is on the table. I put the flowers into the vase.)

3. Liegen (to lie):

- Accusative: Die Bücher liegen auf den Regal. (The books lie on the shelf.)

- Dative: Die Bücher liegen auf dem Regal. (The books lie on the shelf.)

4. Legen (to lay/put):

- Accusative: Sie legt das Buch auf den Tisch. (She puts the book on the table.)

- Dative: Das Buch liegt auf dem Tisch. Sie legt das Buch auf den Tisch. (The book is on the table. She puts the book on the table.)

5. Sitzen (to sit):

- Accusative: Der Mann setzt sich auf den Stuhl. (The man sits down on the chair.)

- Dative: Der Mann sitzt auf dem Stuhl. (The man is sitting on the chair.)

6. Setzen (to set/put):

- Accusative: Ich setze die Tasse auf den Tisch. (I set the cup on the table.)

- Dative: Die Tasse steht auf dem Tisch. Ich setze die Tasse auf den Tisch. (The cup is on the table. I set the cup on the table.)

You might notice that the differences between “lay” and “lie” and “legen” and “liegen” compare to the differences in English of similar sounding verb pairs. “Lay” is an example of an transitive verb, which requires a direct object, the same as “legen”. “Lie” is an intransitive verb, which will not use a direct object, the same as “liegen”.

Common Mistakes

One prevalent error among English speakers learning German revolves around the confusion between German and English prepositions. An example involves the German word “bei,” which sounds similar to the English counterpart “by” and shares a similar meaning when denoting proximity. However, it is crucial to recognize that the German “bei” doesn’t correspond to the English word in other contexts or forms.

Another common pitfall emerges when English learners of German attempt to substitute English prepositions one-for-one. Unfortunately, this approach often leads to inaccuracies in expression. While some prepositions may appear similar in both languages, their usage and nuances can differ significantly. A direct swap of English prepositions for their German equivalents may result in sentences that sound awkward or convey unintended meanings.

So, overcoming these challenges requires a good understanding of each preposition in its German context, recognizing that subtle differences in usage exist between the two languages. Rather than relying on direct translations, learners benefit from immersing themselves in authentic language use and familiarizing themselves with the specific contexts in which German prepositions are employed.

Key Takeaways

Here is also a brief formula on the sentence structure of how and when we use accusative prepositions and when we use dative prepositions in German.

Action Verbs (setzen, stellen, legen, hängen) + Accusative Direct Object (= the thing being moved) + Two-way Preposition with Accusative (answers the question WOHIN?) ➜ Someone (A=subject) places an object (B=direct object) somewhere (C=prepositional phrase).

Position Verbs (sitzen, stehen, liegen, hängen) + Two-way Preposition with Dative (answers the question WO?) ➜ An object (A=subject) is in a specific location (B=prepositional phrase).

Let the Flamingos Loose

Now, the first step is always the hardest and that is to memorize the two-case prepositions. Harry Bum Tschak and Jean-Baptiste Castel have worked with me to create music and a video to help you memorize the two-case prepositions. Which led to this gorgeous music video. Let us know on Youtube if you like this video!

Do you want to learn the moves?

If you watched this video and you want to dance along…. here are the moves:

vor – in front of – hands in front of you

hinter – behind – hands behind you

über – over – hands over your head

unter – under – hands down/under

neben – next to – hand as in Beyonce’s “put a ring on it”

an – on (e.g. the wall) – slap hand to the face

zwischen – between – head between your hands

auf – on top of – one hand on your butt

in – in(to) – hold your arms above your head, grab your elbows; build an “o” with your arms and put your head inside the “o”.

FAQs about German grammar, two-way prepositions and learning the German language

Here are some of the questions people ask about German prepositions and the process of learning the language.

What are the rules for prepositions in German?

German prepositions can be challenging as they govern different cases (nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive). The choice of case often depends on whether the preposition indicates location, direction, time, or possession.

What are directional prepositions in German?

Directional prepositions in German indicate movement or direction. Common examples include “nach” (to), “zu” (to/towards), and “in” (into). The choice of case depends on the specific preposition and the context.

What are the 9 prepositions in German?

There are more than nine prepositions in German, but some common ones include “an” (at/on), “auf” (on), “über” (above/over), “unter” (under), “vor” (in front of/before), “hinter” (behind), “zwischen” (between), “neben” (beside), and “in” (in/into).

What are the two-way prepositions in German?

A two-way preposition in German can take either the accusative or dative case, depending on whether the motion or action involves a change of location (accusative) or a location without movement (dative). Examples include “in,” “auf,” “an,” and “hinter.”

How do you use Wechsel prepositions in German?

“Wechselpräpositionen“ (also called “two-way” or ”dual prepositions”) in German can be challenging. When indicating motion or change of location, they take the accusative case. When describing a location without movement, they take the dative case. It’s crucial to understand the context and whether the preposition implies movement or static position.

Summing Up: German Two-Way Prepositions

So, there you have it! Navigating the twists and turns of German two-way prepositions with the help of Michael Schmitz doesn’t have to be a head-scratcher.

You have hopefully seen the difference between accusative and dative prepositions and learned the basic rules on when we use each. Learn all about fixed cases and unravel sentence structures to turn German grammar from a potential headache into a stress-free language adventure.

With Michael’s tips, you’re not just learning – you’re rocking German two-way prepositions effortlessly. Come check out our courses on SmarterGerman to see what we mean!