Learning German does not just help you get a job with Lufthansa or book a hotel in Frankfurt. Learning German is also a passport into another world. And part of this world is the world of stories; everything from modern crime stories (Krimis like ‘Die Tote Frau’ in smartergerman) or going back to some of the most well-known fairy tales put together by the Brothers Grimm. Of course, most of these have been translated into English and we have enjoyed them being read to us when young, and we have enjoyed reading them to our own children when old, but translation brings them into our world. If we really want to be transported, we need to step into the language.

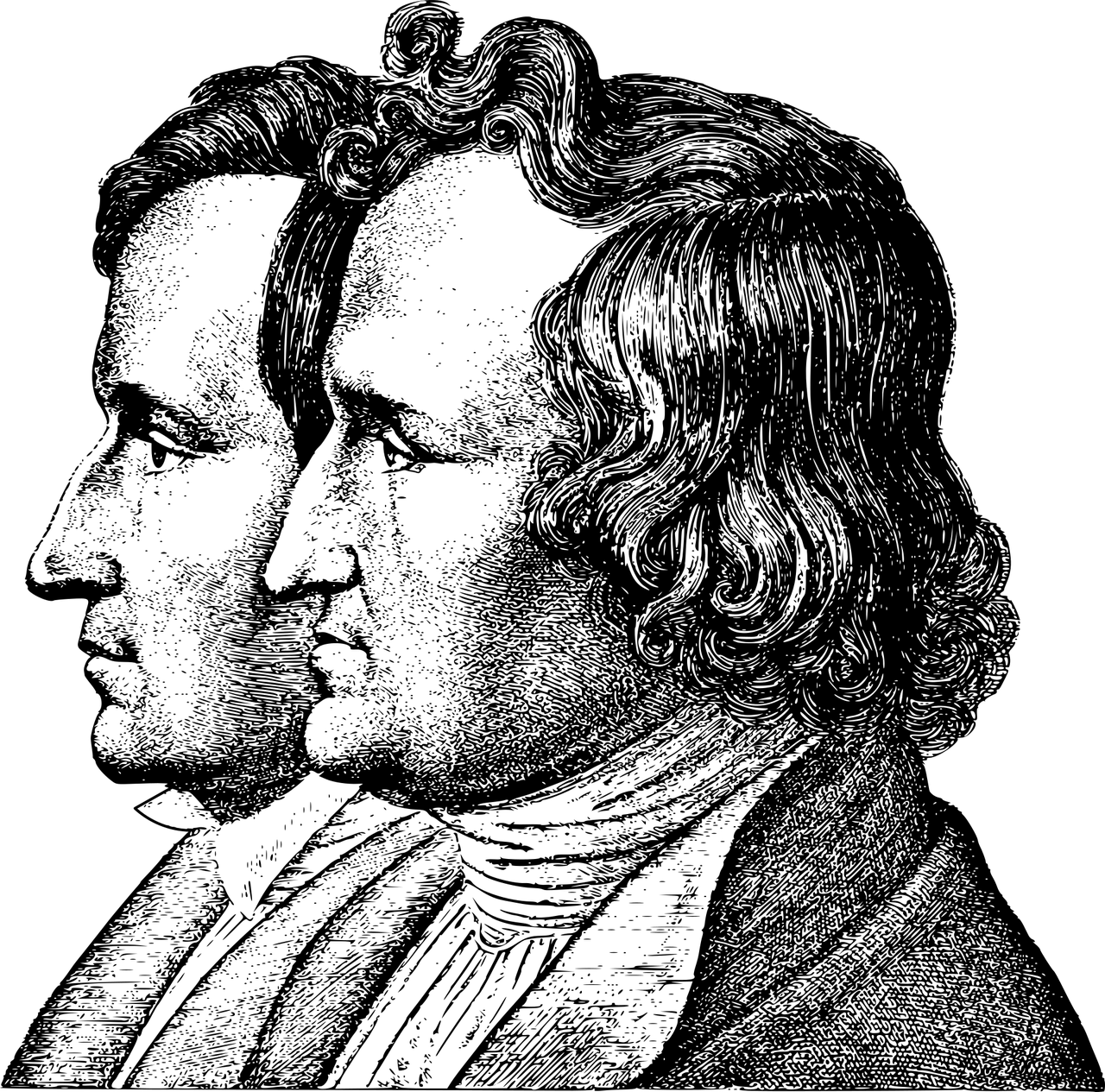

The Brothers Grimm, Wilhelm and Jakob Grimm, were historians and philologists (the study of languages in relation to story-telling) and they collected old stories from Germany and surrounding European countries. It was really the history of the Germanic languages and their German dictionary that was their life’s work, but at the height of romanticism, their collection of fairy tales became popular. They were not originally meant for children, but were later shaped to fit the audience. Even so, some of them were considered inappropriate and had to be changed further … and even these are considered by some too violent for children of today, particularly in relation to Disney-versions of the stories.

The Grimms believed in these stories as foundational elements for the culture of Germany; that a sense of being German was tied up in the many stories that had been told from generation to generation by word of mouth. Like with any old story, there were often many different versions of similar stories in different places, so part of the process of collecting them was to decide upon how to put a single story together from all the various parts.

These even changed from edition to edition of their works. The collection called Kinder- und Hausmärchen went through several different editions and became more and more popular as the years went by, and a greater sense of Germanic unity developed. The book became such a symbol of German nationalism that it was even banned for a short period after the Second World War.

However, they never did finish their German dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch), since they spent so much time and effort researching every word. They only got up to the letter ‘F’.

One of my favourite fairy tales collected by the Grimms is ‘The Pied Piper’ which is called ‘Der Ratenfänger’ in German, which is already an interesting point of difference in emphasis.

It was Robert Browning’s version of it that I remember so well, but there are many different versions that developed over time and place. In fact, the original version doesn’t even mention rats at all. Children were taken by a brightly dressed chap. And it might not have even been children; in its context, it could have meant ‘children’ as meaning being a child-of a place, or having been born there. It could well have been recording a mass migration into the underpopulated eastern regions of Europe, perhaps encouraged by a brightly dressed ‘procurer’. People were certainly not so mobile in the early middle ages, so such a migration would have been a noteworthy event.

Perhaps Robert Browning’s English version will always be my version of the story. But learning German helps you realise how much our stories are tied up in our languages, which was really the whole point of the Grimm project anyway. The Grimms took these fairy tales, these ancient stories from oral sources in every kind of dialect and variance, and managed to teach them German.

So now, it’s our turn.

This post was written by Jeremy Davies