The Problem of Humanizing Adolf Hitler

For all his infamy, Adolf Hitler remains something of a mystery, even in the 21st century. From humble origins as an aspiring Austrian artist, his rise as a soldier, activist, politician, and eventual dictator more often highlight the atrocities he committed, and gives little to no attention to the life he lived up to that point. In fact, it wouldn’t be a stretch to insist that by doing so, it might humanize an otherwise deplorable man, strip away the aura of hatred both from and levied upon him, and situate him as one small part of a massive machine dedicated to avenging the outcomes of history.

An Unlikely Source of Insight

Which is why it surprises me to no end that the finest, most accessible biography of “history’s greatest monster” comes to us courtesy of an unlikely source: Japanese mangaka Shigeru Mizuki. Like the eventual dictator, Mizuki had humble origins- growing up in rural Japan, at a time when the country was fast on the rise to the war that would eventually consume it at the midpoint of the 20th century.

Like the Austrian, he was a talented artist, but one who had a temper that often got him into trouble. Like Hitler, he entered the military during a period of aggression on the part of his homeland, and as a result suffered from the worst mankind had to offer. And indeed, Mizuki was known as being somewhat obsessed with the man who drew the world into war, dedicating numerous volumes of his illustrated war histories to Nazi Germany and its charismatic leader.

Before the Second World War

In the late 19th century, German-Japanese relations soured due to Germany’s imperialist ambitions in East Asia. The Triple Intervention in 1895, led by Russia, France, and Germany, urged Japan to refrain from acquiring Chinese territories awarded in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, causing friction. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904/05 strained relations further, as Germany supported Russia, triggering distrust on the Japanese side.

By the onset of World War I, relations had deteriorated significantly. The Japanese government, seeking to reduce European colonial influence in Southeast Asia, declared war on Germany in 1914, aligning with Britain, France, and Russia. The major conflict between the Japanese military and Germany occurred during the siege of Tsingtao in China, where German forces resisted a Japanese/British blockade until November 1914.

Japan, as a signatory of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, gained German territories in the Pacific, including islands and Kiautschou/Tsingtao in China. The treaty’s transfer of German concessions in Shandong to Japan sparked outrage in China, leading to the May Fourth Movement and influencing China not to sign the treaty. This contributed to Germany viewing China, rather than Japan, as its strategic partner in East Asia in the following years.

Escalation of Tensions

Amidst the complex geopolitical landscape of East Asia, the deteriorating relations between Japan and China culminated in the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. This conflict arose as China resisted Japan’s expansionist ambitions that had commenced in 1931. The war, officially undeclared until December 9, 1941, unfolded in three distinct phases: a period of rapid Japanese advancement until the end of 1938, a subsequent virtual stalemate until 1944, and a final stage marked by Allied counterattacks leading to Japan’s surrender.

The roots of this conflict trace back to Japan’s effective control of Manchuria in the early 20th century, initially established through the Twenty-one Demands in 1915 and later sustained by supporting warlord Zhang Zuolin. Tensions escalated as the Chinese in Manchuria resisted Japanese privileges, despite the region’s legal title being held by China. The friction intensified with the construction of Chinese railroads aiming to encircle Japanese lines, prompting the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931, known as the Mukden Incident.

The Japanese seized Mukden, establishing the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932 with the deposed Qing emperor Puyi as its nominal head. Japan’s ambitions extended beyond Manchuria, as evidenced by a Tokyo pronouncement in 1934, effectively declaring all of China as a Japanese sphere of influence. In 1935, Japan forced the withdrawal of officials and armed forces from Hebei and Chahar, placing these territories partly under Japanese control and posing threats to Suiyuan, Shansi, and Shantung.

As tensions heightened, Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader, pursued his campaign against Chinese communist forces, avoiding open opposition to Japan. However, the Xi’an Incident in December 1936 compelled Chiang, seized by forces under his own generals, to form a United Front with the communists against the common threat posed by Japan.

Germany, Japan, and China

In the aftermath of the Nazi Party’s rise to power in Germany in January 1933, significant strains emerged in German-Japanese relations. The SA, a para-military branch of the NSDAP, targeted Asian students at German universities, leading to complaints from Japanese and Chinese officials about “Yellow Peril” propaganda, reports of plans to ban interracial relationships, and violence against Asian students. The Japanese government, in October 1933, and the Chinese government, in November 1933, issued warnings against visiting Germany, citing safety concerns for Asians.

German Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath intervened to halt SA violence against Asians, emphasizing the potential expulsion of the German military mission from China. While Germany had closer relations with China at this time, Neurath highlighted the advantage of having Japanese elite students studying in Germany for long-term benefits. In late 1933 and early 1934, another strain emerged when the German ambassador to Japan, Herbert von Dirksen, supported the appointment of Ferdinand Heye, a Nazi Party member, as the Special German Trade Commissioner for Manchukuo. Hitler disavowed Heye, aiming to maintain Germany’s delicate relationship with China.

In the summer of 1935, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Japanese military attaché General Hiroshi Ōshima considered an anti-Communist alliance involving Germany, Japan, and China. However, this approach was vetoed by the German Foreign Ministry, prioritizing trade relations with China.

The signing of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in June 1935 caused a temporary deterioration in German-Japanese relations, as some Japanese leaders perceived it as Germany attempting to ally with Great Britain. Despite Hitler’s recognition of Britain as a potential ally, he also identified Japan as a target of “international Jewry” in Mein Kampf, suggesting a complex diplomatic landscape.

Shifting Alliances and Strategic Dilemmas

While initial plans for a joint German-Japanese strategy against the USSR were hinted at in the 1936 Anti-Comintern Pact, the pivotal years of 1938 and 1939 played a decisive role in Japan’s shift from considering a northern expansion against the USSR to focusing on southern expansion. Defeats in the Battles of Lake Khasan and Khalkin Gol against the Soviets convinced Japan that its military, lacking heavy tanks, was ill-equipped to challenge the Soviet Army at that time.

Despite this, Hitler’s anti-Soviet sentiment led to renewed cooperation with Japan, as he anticipated Japan’s participation in a future war against the Soviet Union. However, Hitler’s frustration with Japan’s prolonged negotiations with the United States and its reluctance to engage in a war with the USSR led to a temporary collaboration with the Soviets through the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939.

The pact, kept secret from Japan and Italy, strained German–Japanese relations, leading to the signing of the “Agreement for Cultural Cooperation between Japan and Germany” in November 1939 to ease tensions. As Japan continued its expansion plans, its conflicts with China and the invasion of northern French Indochina in September 1940 escalated tensions with the United States. The U.S. implemented the Export Control Act in July 1940, imposing sanctions on Japan. Misinterpreting these actions as a need for radical measures, Japan found itself drawing closer to Germany.

Complex Motivations

In December 1941, a pivotal month in World War II, historians often focus on Imperial Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent U.S. Declaration of War. However, equally significant were the Red Army’s counterattacks against the Germans and the declarations of war by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy on the United States. These events, occurring within a week, transformed the conflict into a global conflagration.

The question arises: Why did Hitler and the Nazi regime hastily declare war on the United States just four days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor? This decision has puzzled historians, considering the ongoing resistance in Europe and the precarious situation on the Eastern Front. The perception of Japan in Germany’s racial worldview, Hitler’s understanding of the United States before 1941, and the contextualization of the choice to go to war must be examined.

The representation of Japan in German culture played a crucial role, with decades of a peculiar imagining. Additionally, understanding how Hitler perceived the United States before 1941 is essential. The decision to go to war with America, seen as a choice, must be embedded in the tumultuous events of 1941, including the transition from mass murder of Jews in Eastern Europe to continent-wide genocide.

Hitler utilized Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor as a pretext to escalate the conflict on the German side. The war transformed into a global struggle for racial supremacy, with Hitler viewing it as a battle against a coalition of enemies believed to be uniformly under the influence of “the Jews.” This interpretation of history reached a radicalized stage in December 1941, marking a definitive shift for the Third Reich.

Transnational Nazism

In his book, “Transnational Nazism, Ideology and Culture in German-Japanese Relations, 1919–1936,” Ricky W. Law of Carnegie Mellon University explores the perplexing alliance between Japan and Germany during World War II. Addressing the question of how these nations, driven by aggressive and anti-foreign ideologies, became allies, Law delves into cultural and media sources from both countries.

The German Japanese Alliance

Analyzing newspapers, films, magazines, and textbooks in three languages, he reveals that intellectuals and commentators from Japan and Germany were shaping a positive image of each other even before the official alliance in 1936. The cultural admiration stemmed from Japan’s appreciation of Germany’s military strength, territorial expansion, and charismatic leadership. Law emphasizes that this alliance, while strong ideologically, faced practical challenges due to the considerable distance between the two countries.

Despite minimal travel and communication, Japanese intellectuals actively influenced German ideals for Japanese consumption of Hitler and Nazism. Law draws parallels to contemporary issues, noting the enduring and flexible nature of Nazism as an ideology, with modern supremacists appropriating and disseminating elements reminiscent of the 1930s Japanese media strategies. “Transnational Nazism, Ideology and Culture in German-Japanese Relations, 1919–1936” is Ricky Law’s first book, published by Cambridge University Press.

Japanese Culture in Germany

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 marked a significant turning point in the relationship between Germany and Japan. Prior to this conflict, Japanese interest in German affairs was not reciprocated. However, Emperor Meiji’s victory over Russia drew attention worldwide, particularly in Central Europe.

In Germany, a fascination with Japanese culture emerged, particularly on the Right, emphasizing the samurai, Bushido, martial arts, and Japan’s attempt to blend modernity with tradition. Karl Haushofer, a Bavarian General Staff member and geopolitics theorist, spent time in Japan, shaping a narrative of shared martial virtues and struggles against modern cosmopolitanism.

Despite Japan’s intervention in World War I against Germany, the subsequent acquisition of German territories did not disrupt exchanges. Many Germans found an affinity with Japan due to a common disdain for postwar treaties by the Western Allies.

Adolf Hitler, in the 1920s, praised Japan’s naval policy, reflecting concerns about the size and capability of the Japanese navy shared by imperialist states. Hitler’s views on Japan evolved, acknowledging Japan’s modernization influenced by Aryan origin but contorting this acknowledgment within his racist framework. He predicted Japan’s cultural decline without continued Aryan influence.

By 1933, Hitler increasingly admired elements of Japan’s political, economic, and military power, though his racist perspective persisted. The Shōwa Era’s onset, the rise of ultra-nationalists in Japan, and its move into Manchuria fueled Hitler’s enthusiasm for a Berlin-Tokyo Axis in the mid-1930s. While he never fully repudiated Mein Kampf, Hitler effectively revised his racism to justify the alliance.

Mizuki’s Take on Germany

Japan has a rich tradition of inserting Germany into their media works. Much of the time, it is to depict the impact as largely negative – criticism of fascism or oppression, or thinly veiled insistences that Germany was the cause of Japan’s downfall, whether accurate or not. But in the case of Mizuki, a man who was harshly critical of both the war and the actions committed by both Japan and the European Axis powers, his even-handed look at those dark years provides another voice in the debate: one that argues history is its own largest foe.

© via Pixabay

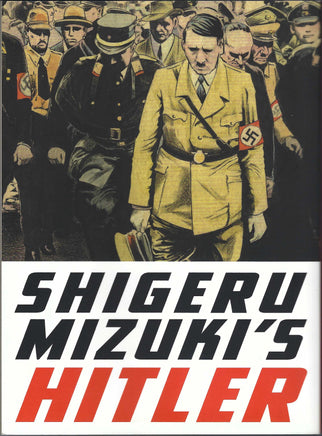

Hitler Mangas

“Hitler,” his massive work looking into the life of the man, is no different than his other war works, save in one regard. Rather than try to paint into the story of the man a sense of the futility of war, he spends far more time trying to understand or relate the motivations behind what caused this artist to become a despot.

Mizuki himself lost an arm in the war, and yet still dedicated himself to becoming the artist he knew he could be. In the manga, he shows Hitler as being lost in his own failures, obsessing over what he didn’t, or couldn’t, have, and using that as a launching point for his political and activist career.

Mizuki’s “Gekiga Hitler”

Shigeru Mizuki’s manga, originally titled “Gekiga Hitler” (劇画ヒットラー, Gekiga Hittorā), was serialized in Weekly Manga Sunday starting in 1971. The English version, translated by Zack Davisson and published by Drawn & Quarterly in November 2015, was derived from a French version rather than a direct translation from Japanese.

Olivier Sava of The A.V. Club notes that Mizuki portrays Hitler as he truly was and as he perceived himself. Sava characterizes this depiction as “dopey, sad, and often pathetic,” highlighting Hitler’s constant inner turmoil. Davin Arul of The Star describes Mizuki’s trademark style of blending cartoonish characters with realistic, highly-detailed settings.

The book’s narrative frames the Holocaust at the beginning and end, with Mizuki using it as a bookend rather than a central focus. Jan-Paul Koopman of Der Spiegel observes a relatively limited exploration of the Holocaust and WWII in the graphic novel.

The English version of the graphic novel includes a two-page list of dramatis personae and a fifteen-page footnote index. Originally serialized from May 8 to August 28, the single-volume was released on March 1, 1972. Drawn & Quarterly announced the English translation in 2014, and the German edition was published in 2019 by Reprodukt with a foreword by Jens Balzer.

Publishers Weekly praises it as a “fresh take” and a “candidate for the year’s best graphic novel.” Despite an initially jarring cartoonish art style, Davin Arul suggests readers become accustomed to it, noting the complexity of the work’s detail, which may pose a challenge for some readers.

Mizuki’s Depiction of the Führer

Unlike other histories of the war or the man, Mizuki’s Hitler doesn’t focus on the atrocities of the Holocaust or the Second World War, or the sting of Allied defeat. Rather, it shows Hitler as an almost farcical version of the newsreel footage. While surrounded by friends and political foes modeled on the actual figures, Hitler is himself comically designed, and prone to expressing his anger with humorous outbursts.

When he is serious, his face darkens but retains its almost grotesque proportions. He questions himself constantly through internal monologues, and celebrates his victories with near-juvenile aplomb. Even at the end, when the war has turned in his favor and he secludes himself deep underground, his weakening morale is tempered with an almost jester-like countenance, where he resigns himself to his fate, while insisting that those around him whom he loves and respects must live for a future Germany, a future he once emphatically swore would never come to pass.

In this, Mizuki manages to create a Hitler that is far more human. While the mangaka does not attempt to reconcile or explain away the evils the man perpetrated (though he does ignore the Holocaust almost entirely and barely mentions a “final solution” to Hitler’s own rantings against the Jewish people), he does his best to show the doubtful, fearful, arrogant, and emotional sides to his subject. He forces readers to get inside Hitler’s head, push away historical assessments of the man, and see plainly what could have driven a human from creative pursuits to destructive impulses.

A Broader View on World War II

Personally, I think that this version of the Great Dictator is one that is worth reading, and is important for its ties to another Axis nation. The fact that a Japanese author used a distinctly Japanese medium to highlight the intricacies of a German figure for a world audience is reason alone to give this volume a look. Growing up as an American boy in the public schools, we never tried to study Hitler the man, just Hitler the monster. And while some of what I read in Mizuki’s manga was old news, I found the fact that it was present rather fresh.

We take for granted the history behind the war, but it is itself worth studying, as it showcases turbulent times and complex emotions and politics that eventually allowed for such an extreme case of fascism to thrive. Looking at the reluctance of President Hindenburg, or the machinations of Schleicher, or seeing Hitler’s reactions to the death of his niece, it gave focus to the events and peoples that influenced both Hitler and his cronies, and gave rise to their rhetoric and eventual dominance.

And, in the end, showed the consequences of that arrogance, as their world burned around them. No longer mysterious or frightening, just another instance of human drama.

Enjoyed the history lesson? There’s more where that came from! Come check out our German history series.

FAQs about Hitler and Nazi Germany

Here are some of the questions people ask about Nazi Germany and the German-Japanese alliance.

What is the relationship between Germany and Japan?

The relationship between Germany and Japan is characterized by diplomatic cooperation, economic ties, and shared values. Both nations maintain strong bilateral relations, often collaborating on issues such as trade, technology, and global governance.

Did Japan fight alongside Germany in WW2?

Yes, Japan and Germany were both part of the Axis powers during World War II. While they cooperated diplomatically and shared certain strategic objectives, their theaters of operation were largely separate. Japan focused on the Pacific and East Asia, while Germany operated in Europe and North Africa.

Why did Germany lose against Japan?

Germany did not directly engage in military conflict against Japan during World War II. The defeat of Germany was primarily due to a combination of factors, including strategic mistakes, resource shortages, and the overwhelming military power of the Allied forces, particularly the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front and the United States and its allies in the West.

How did Japan react to Germany’s surrender?

Japan reacted to Germany’s surrender in 1945 with a mix of shock and concern. The news contributed to a sense of isolation for Japan as its Axis ally succumbed to defeat. However, Japan continued its own war effort until August 15, 1945, when it announced its surrender to the Allies, marking the end of World War II.

How does Shigeru Mizuki’s manga handle the topic of Jews in Eastern Europe?

Mizuki’s manga was primarily focused on Hitler’s life and minimally addresses the Holocaust and Jews in Eastern and Central Europe. It mostly explores Hitler’s character and motivations, often sidestepping the explicit horrors of German war crimes and the Holocaust.

Summing Up: Japan’s Relationship with Hitler

In Shigeru Mizuki’s manga on Hitler, we unearth a unique portrayal that humanizes the infamous dictator. Amidst the broader historical context of Japan’s intricate relations with Germany, this narrative challenges conventional views, offering insights into Hitler’s doubts, fears, and emotional complexities.

The transnational alliances, shifting strategies, and cultural dynamics explored in this journey through history provide a richer understanding of WWII and the ideological underpinnings that bound these two nations and their respective governments. As Mizuki’s manga brings Hitler to life, it not only reflects on the past but invites readers to reassess historical figures beyond their monstrous deeds.

The broader view on World War II and Nazi Germany, incorporating the perspectives of various nations, offers a comprehensive narrative that goes beyond the surface, emphasizing the importance of studying the intricate web of events, emotions, and politics that shaped this tumultuous period in human history. If you’d like to learn more about German culture and history, come check us out at SmarterGerman!